After being caught smoking marijuana in school, a graduating student from Krus Na Ligas High School was sent by a teacher to the Quezon City Anti-Drug Abuse Advisory Council (QCADAAC) for six months of rehabilitation.

“Bakit niyo ako dadalhin dyan? Hindi ako adik (Why are you sending me there? I’m not an addict),” Rommel Perez, the teacher, recalled the student’s reaction.

Over the next six months, Perez and the student’s class adviser would visit her at the rehab center every Friday to pick up her completed school work and drop off new modules, enabling her to finish her studies on time.

Rommel Perez, a “guidance teacher” at Krus na Ligas High School.

Came graduation day, the student was allowed to leave the center to march with other graduates. She hugged Perez as he handed her diploma onstage and told him: “Sir, kung hindi ako nakinig sa inyo, wala ako ngayon dito (Sir, had I not listened to you, I wouldn’t be here now).”

In this and several instances, Perez had performed the role of guidance counselor when he was not supposed to. He is not a licensed or registered guidance counselor, and was hired by the Department of Education (DepEd) as a teacher.

Republic Act (RA) 9258, the Guidance and Counseling Act of 2004, sought to professionalize the practice of guidance and counseling by prohibiting nonregistered individuals like Perez from practicing guidance and counseling. Enacted in 2004, RA 9258 punishes violators with imprisonment of up to eight years or a fine of up to P100,000.

But for lack of a registered guidance counselor at Krus na Ligas High School, the principal assigned him to be the guidance counselor and gave him the title “guidance teacher” to go around the law.

Many schools in Quezon City and elsewhere in the country are in the same boat for several reasons.

It is impossible to enforce RA 9258 at present or in the near future: The number of registered guidance counselors in the country falls far, far below the sheer number of schools and institutions mandated to hire them.

Schools and institutions that violate the law also get away because its chief implementer, the Professional Regulatory Board of Guidance and Counseling (PRBGC), does not monitor lawbreakers.

Neither does DepEd compel schools to meet the law’s requirements. This makes the penalties under RA 9258 only good on paper.

Under DepEd’s staffing standard, public and private elementary and high schools are required to hire one guidance counselor for every 500 students.

The country, however, suffers from a severe shortage of registered guidance counselors (RGCs) for schools to meet the standard. Since the first batch of licensure examinees in 2008, it only has 3,220 RGCs nationwide as of July 2017.

The low number of RGCs has been attributed to the high educational attainment RA 9258 sets for licensure examinees. Only a bachelor’s degree is needed to take the Licensure Examinations for Teachers (LET). A master’s degree, however, is required of guidance counselor examinees.

To meet DepEd’s requirements, a total of 46,959 RGCs are needed. That means a shortage of 43,739 in the basic education sector alone.

How many registered guidance counselors do elementary and high schools need?

The DepEd Youth Formation Division has practically given up on achieving the staffing standard.

“Siguro yung ganoong setup, it’s feasible sa private schools. Pero sa public schools, to be honest, hindi masyado (That setup could be feasible in private schools. But in public sc hools, to be honest, not so much),” said Jennifer Pascua of the division.

Statistics show public schools need at least 41,000 RGCs, private schools at least 5,000 RGCs and those run by state universities and colleges (SUC) at least 100.

Quezon City, for example, has 46 public high schools with a student population of almost 146,000. Should DepEd’s 1:500 staffing standard be followed, there should be 290 guidance counselor positions.

But for schoolyear 2016-17, only 25 people were hired as guidance counselors by the Quezon City Schools Division Office. Of the 25, only nine are RGCs.

Cecilia Rufon of the Quezon City Schools Division’s Personnel Section said few people apply as guidance counselor in Quezon City. She added the division has stopped accepting unlicensed applicants since the passage of RA 9258.

“Usually naga-apply silang guidance counselor pero ang tinapos nila hindi naman guidance; mga teacher (Usually the applicants don’t have a degree in guidance; they’re teachers),” Rufon said.

And many of those hired as teachers end up like Perez. “Na-hire naman sila as teacher pero ang trabaho nila sa field, more on guidance (They get hired as a teacher but their work on the field is more on guidance),” Rufon said.

Compensation is a major reason applicants prefer to be teachers than guidance counselors. Despite being armed with a master’s degree and a license, guidance counselors in public schools are assigned only three salary levels and draw a basic pay of from P18,217 to P21,387 a month.

Teaching positions, on the other hand, have up to seven levels, giving teachers more opportunities to get promoted to higher-paying positions.

While the starting salaries of a guidance counselor and a teacher both start at P18,217, a teacher can earn as much as P39,151 in basic pay as master teacher. On top of that, teachers are not required to have a master’s degree before they can start their career.

Salaries: Guidance counselors versus teachers

Gilore Ofrancia, a former guidance counselor, criticizes RA 9258 for requiring guidance counselors to have a master’s degree.

“Kung ikaw ay bagong graduate (If you are a fresh graduate), would you rather choose na mag-master’s (to take up master’s) to take the guidance and counseling board exam or just pass the LET and enter the public school as Teacher 1?” he said.

Ofrancia is not a licensed guidance counselor and was hired before the law was passed in 2004.

Guidance counselors hired before the passage of the law got to keep their jobs but are no longer eligible for promotion if they continue to hold a guidance counselor item. To be promoted, they need to change their items to become teachers, but that would send them back to a Teacher 1 position.

Elena Santos, also of the Quezon City Schools Division Personnel Section, said guidance counselors who are unlicensed but were hired before RA 9258 have been allowed to keep their posts because of their permanent employment status and security of tenure.

She also said the Professional Regulatory Board of Guidance and Counseling (PRBGC) does not coordinate with DepEd on the implementation of the law.

PRBGC Chairperson Luzviminda Guzman acknowledged the board does not monitor schools’ compliance with RA 9258.

“It should really come from the (school) head. If they’re already aware of the law, that should already be their role (to report),” she said.

Guzman added the PRBGC does not check if the guidance counseling program prepared by DepEd follows its code of ethics.

“Instead of questioning immediately, nandun na rin yung trust (we trust them) because we have guidance counselors there who are working (in DepEd),” she said.

A few unregistered guidance counselors in public high schools do try to comply with RA 9258.

One of them is Cleopatra Daisy Aguinaldo, a guidance counselor at Quezon City’s Sergio Osmena Sr. High School for 15 years. She went back to school to get a master’s degree in guidance and counseling, took the licensure exam and obtained her license in 2016.

She said, however, she did not gain much by becoming an RGC.

“Parang ine-expect ko kasi before na kapag RGC ka, mas…hindi lang sa compensation eh… Yun bang mabigyan kayo ng enough attention (I used to expect before that when you’re an RGC, it’s not just in the compensation, but at the very least, you’re given enough attention),” she said.

Aguinaldo also thought DepEd would shoulder their seminar fees, hold monthly meetings and assign a supervisor at the division office to supervise the guidance counselors. She was wrong.

There are few like Aguinaldo who bother to get licensed as guidance counselor. Because of the dearth of RGC in elementary and high schools, DepEd tried to work around RA 9258. The Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013 allows nonregistered guidance counselors to work as career advocates, provided they first undergo training at DepEd.

“Ang hindi lang naman nila pwedeng gawin (The only thing career advocates can’t do) is counseling,” Pascua said.

Students mostly cannot tell the difference between guidance counselors and career advocates, however, and thus turn to the latter and their teachers for counseling.

And nonregistered guidance counselors like Flordelisa Cerdenia, who works as a guidance designate at the Judge Juan Luna High School in Quezon City, can’t find it in them to turn these students away.

“Siyempre ‘di mo sinasabi na magcacounsel ka. E, pag nagpunta sayo ang bata, ano gagawin mo? Natural, counseling din yun. Angalang ‘di mo tulungan, edi ako pa makasuhan ‘pag may nangyari d’yan (Of course you wouldn’t say you’re counseling. But when a kid comes to you, what do you do? That’s still counseling. I couldn’t ignore them; I might get sued if something happens to them),” she said.

Students at Krus na Ligas High School hardly care that Perez is not a registered guidance counselor.

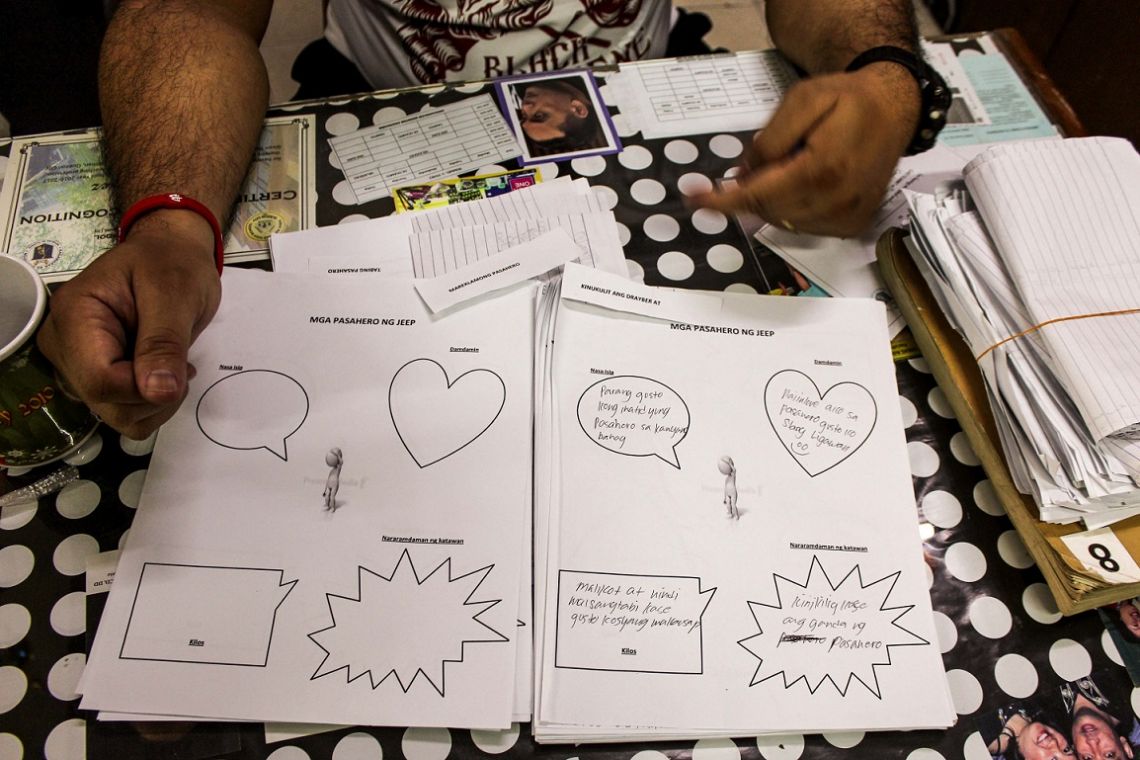

As guidance teacher, Rommel Perez facilitates a “mindfulness” activity to help students relax and understand themselves better. He shows sample worksheets of students.

Besides the student caught smoking marijuana, he has helped many others: the student he talked out of committing suicide, the student who almost got raped and whom he accompanied to court, the student who had a mental condition whom he referred to the Philippine Mental Health Association.

For these students, Perez is their guidance counselor, licensed or not.

(To be concluded)

(This article is a modified version of the author’s undergraduate thesis, “Misguided Counseling?: An Investigative Study on the Hiring and Practice of Guidance Counselors in Public Secondary Schools in Quezon City,” done under the supervision of University of the Philippines journalism professor Yvonne T. Chua last year.)